Image by Gerd Altmann from Pixabay

How will the future of higher education look like in countries such as Finland or Spain? Since the launch of the Bologna process, one of Europe’s key goals has been making higher education competitive worldwide. According to EHESS (European Commission, n.d.), this competitiveness can be measured in terms of two dimensions: a country’s global role in education, and its performance in research and innovation.

Initiatives like the European Universities Initiative aim to strengthen higher education within Member States by attracting students, solving challenges and fostering collaboration in education around hubs for innovation for entrepreneurship, living labs, sustainability or digital transformation among other areas. These programmes are supported by EU Funding (European Commission, 2024), through initiatives like Erasmus + or Horizon Europe. In fact, the European Commission has proposed increasing the Erasmus+ budget to 40.8 billion € in the next EU financial framework for 2028-2034 (European Commission, 2025). However, this ambition contrasts with the positions of some governments in Europe that are currently cutting the funding for Education.

Is Europe going towards academic capitalism?

Funding of universities on metrics for economic results may bring us to academic capitalism. That is what the researcher Mikko Poutanen (2023) claims that the Anglo-American higher education system is following the academic capitalism where the economical metrics are emphasized and set over research and educational goals and the education suffers. Academic capitalism does not mean higher education and universities work like companies, but the border between the public and private sector becomes blurry. However, higher education companies have been founded in Finland, since universities of applied sciences are often limited companies. The owners in universities of applied sciences differ from cities, higher ed institutions to foundations and so forth. The Finnish higher education seeks to respond to the expectations and demands of the society and work life. This is leading to developing the higher education sector towards a business market thinking. (Poutanen, 2023.)

This transformation is not unique in countries like Finland. Universities are racing worldwide for higher positions in university rankings, prioritizing their visibility to attract students and funding within their strategies rather than with their service to society. As Bekhradnia (2016, p.3) says, “rankings -both national and international- have not just captured the imagination of higher education but in some ways have captured higher education itself”.

Funding model for higher education in Finland

The Ministry of Education and Culture steers the funding for higher education in Finland and is main financial source for higher education institutions with funding up to 90% for the field. The higher education institutions have an ongoing interaction with the ministry and keep agreement negotiations on a regular basis. The agreements cover common objectives for the system, key measures for each higher education institution, its profile and core competencies, degree objectives as well as the appropriations allocated based on these. The agreement specifies how outcomes of objectives are reported. (Ministry of Education and Culture, n.d.a).

This funding model urges higher education institutions to performance, action and engagement. The biggest part of the funding is based on the teaching and research performances, and in universities of applied sciences also on development. There is also funding allocated based on strategy, which is developed together with the Ministry and the institution. The purpose of the funding model is to improve quality, impact and productivity in higher education field. (Ministry of Education and Culture, n.d.a).

Figure 1: Picture of core funding model 2021 (Ministry of Education and Culture, n.d.b).

The fundamental bases for the funding model have not changed for the 2025-2028 funding period since the previous one in picture above. The strategical funding will give the institutions more autonomy in the new funding model, where the theoretical universities funding for strategic development and profiling was decreased with 1% while the UAS remains the same. (Ministry of education and culture, 2024.)

According to the OECD report, the future of Finland’s funding model for higher education institutions: Tertiary attainment among 25–34-year-olds increased from 39% in 2000 (when Finland had the fifth — highest attainment levels in the OECD) to 40% in 2021, while the OECD average increased by 21 points from 28% to 48% in the same period (OECD, 2023). The vision 2030 in Finland has been that by 2030 among young people, 50% would attain a higher education degree. However, the rate has conversely dropped again in 2024 to 39 %, according to Education at a Glance report. Finland’s tertiary education attainment rate among young adults (25–34 year-olds) decreased from 40% in 2021 to 39% in 2024, which is below the 2024 OECD average of 48%. The country is one of the only six OECD and partner countries that experienced a decrease in tertiary attainment in this age group. (Education at a glance 2025, OECD, 2025a.)

Funding higher education in Spain

In the case of Spain, the scenario is completely different, as there are 92 Universities (50 public and 42 private) (Ministerio de Ciencia, Innovación y Universidades, 2025) and the funding for public universities is not centralized by the Spanish Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities, but comes mostly from the regional funding (Autonomous Communities) being different for each region, what fosters inequalities among institutions and regions.

Besides, the funding of public universities not only comes from regional funding, which on average represents 65 % of its budget, but also from the students’ fees (17 %), the State (4.8 %) and other sources like investments, research projects, etc. (12.4 %). The criterion for funding depends on the university’s number of students but also on other objectives set aiming to increase quality and excellence of the institutions themselves. This program-contract for funding for those institutions that promote excellence in research, infrastructures and attracting international talent are also common in other countries like France, Germany or Switzerland (Escardíbul Ferrá & Pérez Esparrells, 2013).

Interestingly, universities in larger cities like Madrid or Barcelona, which have more students enrolled, rely more heavily on the students’ fees due to the low public funding received.

These regions have also witnessed a fast growth of private universities in the last years: since 1998, the number of private universities in Spain has tripled. Their funding comes mainly from students’ fees (91%) and private donations, although there is some indirect public funding as well. The increased presence of private universities is a trend in other OECD countries as “private education is slowly becoming more common across all levels of tertiary education” and with 3 percentage points more of graduates from private institutions between 2013 and 2022, Education at a Glance 2024 report shows (OECD, 2024).

In Spain, while the enrolment in undergraduate and postgraduate programmes in public universities has increased by 12% in the last ten years, it has increased a 129% in private universities (not affecting PhD programmes). The Government responded in October introducing a new law to limit the creation and recognition of universities, citing concerns on the quality of some recently created private institutions. The new law (Ministerio de Ciencia, Innovación y Universidades, 2025) requires universities to:

- Invest at least 5% of their budget in research and secure external funding equivalent to 2%;

- Ensure that at least 50% of the faculty members hold a PhD and 60% have accredited research experience (aiming to ensure high-quality education and research and knowledge transfer).

- Have a university’s management team with proven experience in university administration

- Demonstrate financial solvency through a guarantee

- Offer a minimum number of undergraduate, master’s and doctoral programmes, having at least 4,500 students during the first six years.

This new policy is not, however, accompanied with more funding for public universities to enable them to be more competitive. On the contrary, the total funding for public universities has fallen by 14 percentage points in real terms since 2009, which puts public universities in a tough situation and far from the European average. According to Education at a Glance 2024 report, the country’s public spending on higher education was 2.19%, a figure below both the OECD average (2.72%) and the European Union (2.44%) (OECD, 2024).

Figure 2. Government expenditure per full-time equivalent student, by level of education (2022), (OECD, 2025b).

In this context, public Spanish universities lack resources, which makes them less autonomous and puts them in a more difficult situation to attract talent. Within the next 10 years, around 25,000 professors will retire in the Higher Education System, representing 18.1% of the Spanish University’s Professors. Without enough and increased funding or hiring flexibility, universities will struggle to replace them, CYD Foundation’s analysis warns (Fundación CYD, 2025).

Do business oriented practices in higher education alter the purpose of higher education?

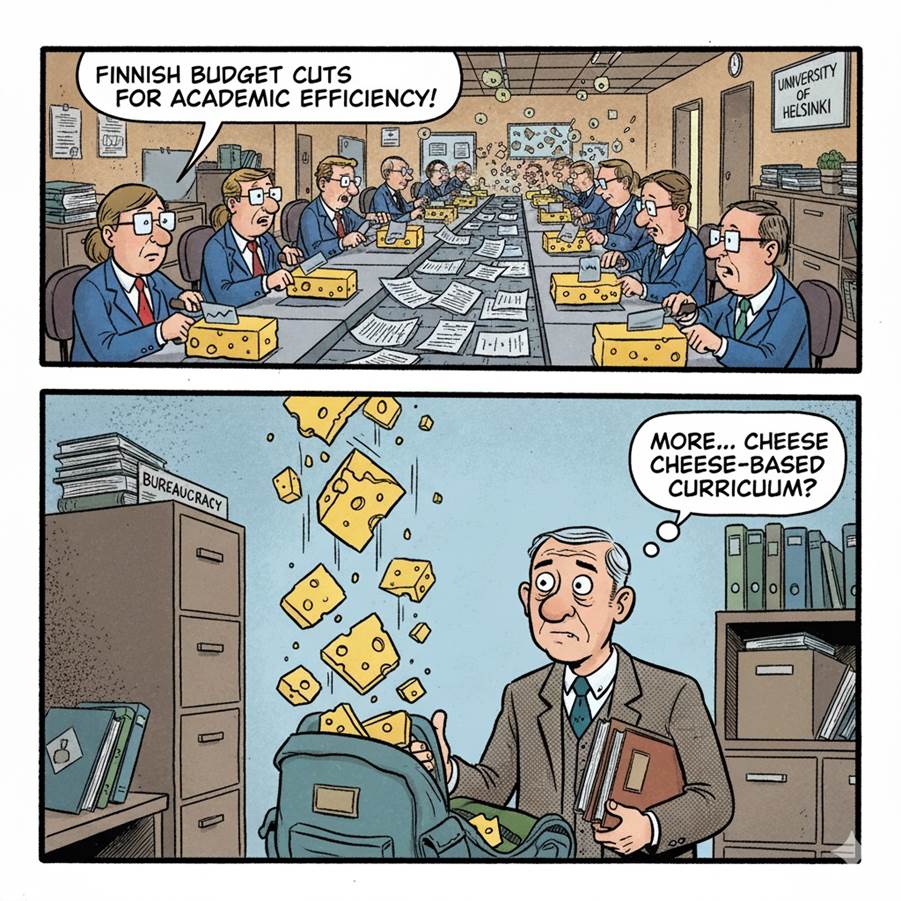

Finland is also facing funding pressure, with a decreased funding of higher education and putting the higher ed institutions in a situation, where there is pressure for them to perform better on a yearly basis because they compete on funding by metrics for performance. There is also pressure for more collaboration, for private funding and accreditation for earlier education. Where does this lead? How does this affect academia? There is also the observation of political decisions in societies leading to pressure for students to get on the fast track in their studies and then into work life. Since the university reform in 2009 higher ed institutions have become independent for their accounting. This has led to institutions having a need to prioritize between profitability and educational goals. The fact is that Finland has under the last 20 years made cuts in education where other countries have invested, even though decision-makers claim they want to invest in education. When looking towards the experience in the USA, this leads to the fact that STEM education is being prioritized and might be seen as more valuable than humanities and arts, which loses in the model of financing. (Ebbe, 2025.)

Illustration on the budget reduction at Finish universities. Created: Gemini, 2025a)

The contribution of students to the universities’ funding is debated in Europe and worldwide. Thirteen EU countries (like Finland) apply a ‘no fee’ regime for all students -including fees below 100 € (Eurydice, 2018) as education is considered a public good, in contrast to other English-speaking countries like United Kingdom and the United States where students pay very high enrolment fees.

Thoughts for the future on funding for higher education in Finland

There has been pressure for enhancing performance within higher education in Finland over the last decades. The government opened the possibility to increase funding through lifelong learning a long time ago, about twenty years ago. After that came the possibility of income through attracting international students and tuition paying students. Since 2017, the funding model has been performance-based. It is called a cheese slicer model, where fund are received on performance, and if not improved in the competition reduced.

One can come to wonder if the next step will be for higher education to decide on tuition fees for national students and students from within the EU to yet again increase funding? What happens in such case to providing higher education equally to all in Finland? Are we beyond that already? And how about the quality of education and research when performance is pressured all the time? The group sizes during studies have become bigger; the pressure for preformed credits is demanding. It is also more common for young people to take a gap year due to the pressure of finding the right field of study and graduating on time. What happens to learning in this funding model for higher education? Now it seems to be chop, chop through education on a fast track – so what will the student learn in the end? When education is becoming to be organized more as business, there is a risk that learning decreases, providing education equally to all members of society diminishes, students are pushed to go through higher education faster and accreditation is getting more common when institutions search more credits fast to meet the goals.

The wellbeing of educators is being affected; results of the development can be seen in the yearly Working life barometer (Melkko & Ilves, OAJ, 2024) by the trade union of education. A few years back and further on this funding model has influenced wellbeing among educators in higher education, especially in universities of applied sciences. Educators within universities of applied sciences experience a bigger workload and higher stress than other educators. Educators need more support in their work, maybe through lecturer teams or mentoring, more support for administrative tasks or support in finding work-life balance, training support for digitalization of education, not to mention effects of AI in education.

In Finland the education is autonomous, and lecturers have big autonomy in organizing and handling their work. One can see that demands are growing on the educators to perform more with less resources, within the work agreement of 1600 hours, which means that educators need to perform more without registering all those hours of work. This will have a profound impact on society if this continues this way without more support for education and educators. Educators have an important role in society, in which education provides experts for work life and innovation through research. Over the last couple of years, there have been several higher education institutions that have been forced to go through change negotiations to cut personnel costs and to streamline processes to keep up with pressure for performance.

The Ministry of Culture and Education in Finland states that the funding model is to improve quality, impact and productivity of education in higher education – is this the case though? Sure, productivity has increased but is it on the cost of learning and teacher wellbeing? Some are questioning the purpose of publishing in universities of applied sciences—how can the impact of UAS researchers’ work be made more visible? The funding model is unique globally when it comes to government funding of applied research in the UAS. How does quality improve when group sizes are getting bigger, and the pressure to perform is growing — what has the student learned? In the end, education is about learning. The greater impact of the Finnish funding model will be seen later as it has now been applied for about 8 years. At this point, it is not possible to say how the funding model will impact higher education or society in the long run.

The increasing demand meets Spanish universities’ limited capacity

In Spain, the insufficient regional funding is hindering public universities from offering an adequate number of places, despite the growing demand. According to the CYD Foundation for Knowledge and Development, in the 2023- 2024 academic year, nearly two students competed for each available seat, what favoured many students turned to private universities.

This situation was more pressing in popular fields such as Medicine, Nursing, and Computer Sciences where the rising demand also met higher admission thresholds. Public universities face other obstacles to create new university seats like major investments in infrastructure and staff or long accreditation processes.

The new law the Government has launched aims to ensure the quality of universities but does not go deeper into the lack of funding public universities are facing. Private universities are not the ones to blame the increased number of students they are having but the question is why are public universities not attracting those students, what measures are they going to make to attract talent and how are they going to work on quality and on ensuring equity among students.

As the think tank Funcas indicates, two steps are needed to provide public universities with the necessary tools to compete with private institutions: increase funding in an efficient and equitable manner and implement a set of measures that ensure greater flexibility, better incentives, and stronger accountability.

Conclusion

Ultimately, the future of higher education funding in Europe seems to be at a turning point. In Finland, the model of tuition-free at higher education is under increasing pressure, as performance-based funding gains traction challenging the principle of education as a public good. One possible step could be the implementation of tuition fees like in other EU countries, even partially, as this could mark a turning point how equity and the role of education are understood in Finland.

In Spain, public universities face rising demand, but the public investment remains far below the European average. Access to the most in-demand programmes depends increasingly on academic records, pushing many students toward private institutions and widening social inequalities. Both cases reveal that the tension between quality, access, and funding sustainability is reshaping higher education—and that Europe must decide whether universities will remain a public good or become a competitive marketplace driven by financial logic.

Author information

Mia Ingman, alumni relations manager, Arcada University Applied Sciences, Finland, with over 20 years of experience from higher education, passionate about learning

Beatriz Manrique has been working as the Director of International Relations Office at Universidad Católica de Valencia, Spain, over the last eight years and is a passionate on promoting internationalisation accross the Higher Education community.

Thank you, Elina Östring and Henna Henrichs for the comments, discussions, insights and collaboration as well as insightful support for this blog.

REFERENCES:

Bekhradnia, B. (2016). International university rankings: For good or ill? HEPI Report 89. Higher Education Policy Institute. https://www.hepi.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/Hepi_International-university-rankings-For-good-or-for-ill-REPORT-89-10_12_16_Screen-1.pdf

Ebbe, J. (2025). Forskning och utbildning hotas allt mer av ekonomiska intressen: ”Vi är väl ingen industri?” YLE article 28.9.2025. Retrieved 29.9.2025. http://yle.fi/a/7-10084534?utm_source=social-media-share&utm_medium=social&utm_campaign=ylefiapp

European Commission/EACEA/Eurydice, 2015. National Student Fee and Support Systems in European Higher Education – 2015/16. Eurydice Facts and Figures. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

European Commission. (2024). Funding for European Universities alliances. Retrieved 11.10.2025. https://education.ec.europa.eu/education-levels/higher-education/european-universities-initiative/funding

European Commission. (2025). The 2028–2034 EU budget for a stronger Europe. Retrieved 11.10.2025. https://commission.europa.eu/strategy-and-policy/eu-budget/long-term-eu-budget/eu-budget-2028-2034_en

European Commission. (n.d.). European Higher Education Sector Scoreboard. Retrieved 11.10.2025. https://national-policies.eacea.ec.europa.eu/eheso/european-higher-education-sector-scoreboard

Escardíbul Ferrá, J.-O. & Pérez Esparrells, C. (2013). The financing of Spanish public universities. Current status and proposals for improvement. Education and Law Review. https://diposit.ub.edu/dspace/bitstream/2445/110820/1/631624.pdf#:~:text=En%20este%20art%C3%ADculo%20se%20analizan%20las%20distintas%20fuentes,y%20potenciando%20la%20transparencia%20y%20rendici%C3%B3n%20de%20cuen-tas

Fundación CYD. (2025). Radiografía del Sistema Universitario Español 1. Docencia. https://www.fundacioncyd.org/la-fundacion-cyd-analiza-la-evolucion-de-las-universidades-espanolas-y-las-caracteristicas-de-su-docencia/

García Montalvo, J., & Montalbán Castilla, J. (2024). ¿Pueden competir las universidades privadas con las públicas en España? Financiamiento universitario y economía política (Papers de Economía Española n.º 180). Fundación de las Cajas de Ahorros (FUNCAS). https://www.funcas.es/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/PEE-180_Garcia-Montalvo_Montalban-Castilla.pdf

Melkko, S. & Ilves, V., OAJ. (2024). Opetusalan työolobarometri 2024. https://www.oaj.fi/ajankohtaista/julkaisut/2024/opetusalan-tyoolobarometri/

Ministerio de Ciencia, Innovación y Universidades. (2025). Estadística de Universidades, Centros y Titulaciones (EUCT). https://www.ciencia.gob.es/InfoGeneralPortal/documento/a8889fb8-fdeb-4a99-8e34-0e922395d42e

Ministry of Education and Culture. (n.d.a). Steering, financing and agreements of higher education institutions, science agencies and research institutes. Retrieved 6.10.2025. https://okm.fi/en/steering-financing-and-agreements.

Ministry of Education and Culture. (n.d.b). Universities of Applied Sciences Core Funding From 2021. Retrieved 6.10.2025. https://okm.fi/documents/1410845/4392480/UAS_core_funding_2021.pdf/1c765778-348f-da42-f0bb-63ec0945adf0/UAS_core_funding_2021.pdf?t=1551281243000

OECD. (2023). Education Policy perspectives. The future of Finland’s Funding model for higher education institutions, p. 4-6

OECD. (2024). Education at a Glance 2024: OECD Indicators, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/c00cad36-en.

OECD. (2025a). Education at a Glance 2025: Finland. https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/education-at-a-glance-2025_1a3543e2-en/finland_d8f44a5b-en.html

OECD. (2025b). Education at a Glance 2025: OECD Indicators, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/1c0d9c79-en

Opetus- ja kulttuuriministeriö. (2024). Korkeakouluille uudet rahoitusmallit. https://okm.fi/-/korkeakouluille-uudet-rahoitusmallit

Poutanen, M. J. (2023). Näkyyvätkö suomalaisen korkeakoulupolitiikan kristallipallossa lukukausimaksut. Poliittinen talous, 11(1), pp. 48–69. https://doi.org/10.51810/pt.125176

Leave a comment